The following is a transcript of our monthly podcast, The Pension Confident Podcast. Listen to episode 44 or scroll on to read the conversation.

Takeaways from this episode

PHILIPPA: Welcome back. Today, we’re looking at the cost of convenience. From Buy Now, Pay Later plans to click-to-buy product tags on Instagram and TikTok, technology makes it super easy for us to shop 24/7.

More than a third of us have used Buy Now, Pay Later, but 41% of those shoppers reported late payment in the last year alone. And what about the long-term debt that you can stack up?

Some experts think all this convenience is blinding us to the psychological and financial consequences of click-to-buy. Today, we’re going to talk about that, and we’re going to share some steps you can take to protect yourself.

Alice Tapper is here with me. She’s the Founder of life and money platform, GoFundYourself, which is also the title of her book. She’s a determined campaign for stronger regulation in the Buy Now, Pay Later industry.

To shed light on the psychology of retail and spending, Tim Hogg is back with us. He’s a Behavioural Economist and Director at research and ratings agency, Fairer Finance.

And from PensionBee, Head of Content Marketing, Dani Skerrett. Hello, everyone.

ALL: Hello.

PHILIPPA: Here’s the usual disclaimer before we start, please remember that anything discussed on this podcast shouldn’t be regarded as financial advice or legal advice. When investing, your capital is at risk.

Now look, I know you’re all financially savvy people, but I’m going to ask you: have you ever used Buy Now, Pay Later?

DANI: Yeah.

PHILIPPA: You have?

DANI: Yeah.

PHILIPPA: Often?

DANI: I went through a few years of using it quite often, yeah. I think I started in a similar way to most people by buying a big high-value item -

PHILIPPA: OK.

DANI: - a piece of furniture. Then I found myself using it quite a lot for silly things, really.

PHILIPPA: How did that go? Did you manage to make the payments?

DANI: Yes, I’d say on the late payment thing you mentioned, I think a lot of people fall into that without realising. I think with the app that I was using, when you pay in three instalments, it automatically comes out. If you pay in 30 days, it doesn’t automatically - you have to physically go on and make the payment.

PHILIPPA: So you don’t necessarily know -

DANI: - so that tripped me up -

PHILIPPA: - do you?

DANI: Yeah, exactly.

TIM: That was my recent experience as well. I use it occasionally. I was setting up with a new retailer, clicked the ‘buy in three’ [option], went through the whole thing, getting approved, clicking all the forms, saying I’d read stuff that maybe I probably hadn’t read in great detail. Yes, yes, yes, put in my address, it gets delivered.

Then I realised I’d never actually set up the repayment plan, and it never told me to do that in that journey. I had to re-log into the app, which is a bit of a faff, and then find out how to put my Direct Debit details in and everything like that. That was a real faff, and I thought, “actually, this is why loads of people end up missing their payments. It’s not because they can’t afford it, it’s just because it’s a bit more friction”.

ALICE: It’s also new. I think so many of us - It’s a relatively new credit product, and there are lots of different providers that do things slightly differently. I’ve used it. I used it when I just bought a house. Life was very expensive, and it’s incredibly useful for those large purchases that you’re going to make one-off, and cash flow is a bit tight for a few months, and it’s actually a really good way of spreading the cost. I’m sure we’ll talk about the pros and cons of it, but I think it can be really useful.

Spending season is here

PHILIPPA: Of course, the timing of this episode, it isn’t any coincidence, Black Friday sales going on right now. Next month, there’s Christmas. Then there’s the January sales. Should we just get a sense of the impact that seasonal spending can have on us? I mean, Alice, how much more do we tend to spend at this time of the year?

ALICE: On average, if you look at the average person, we’re spending about £700 more in December, which is about 30% for most people. It’s a huge increase in the average spend. I think there’s also a huge amount of pressure that lots of us feel to make, particularly with people with kids, to make it this magical time.

PHILIPPA: That probably underrates it, doesn’t it? Because it’s not like we do all our Christmas spending in December.

ALICE: No, exactly.

PHILIPPA: People shop earlier and earlier, don’t they? There’s a long lead up to Christmas now, isn’t it? When you’re probably spending more in the few months in the run up.

ALICE: Well, I think ideally we probably should think about budgeting for Christmas over the year. I think the reality is actually it’s quite difficult to do. The research finds, I think it’s around 50% of people who say that they’re going to use a Buy Now, Pay Later product are probably going to spend the next six months actually paying it off, if not even more than six months.

Actually, it’s July before maybe you’ve paid off your Christmas debt. We’re then even thinking about saving up for Christmas. It’s caught in this cycle. I think it can be really difficult to manage the pressures of Christmas.

PHILIPPA: Yeah, and by that time you’re managing summer holidays. Before you know it, you’re looking at the next Christmas, aren’t you? But the pressure, you may talk about the pressure to make Christmas special. I mean, that’s a big deal, isn’t it? Particularly for families with kids. But generally, the marketing hype around it, I mean, everything urges you to treat yourself, doesn’t it?

DANI: You’re going out to eat more, you’re spending more on drinks, you’re catching up with friends and family, and you want to let people know during that time of year that they’re valued and that you want to spend time with them -

PHILIPPA: It’s true!

DANI: - That’s a pressure, too. It’s not actually just buying presents.

TIM: The other thing about Buy Now, Pay Later is that many more people are Googling the Buy Now, Pay Later providers at the start of December. You see it in the data. It’s like, as Christmas approaches, we know what’s going to happen. We know we’re going to spend more money than maybe we do on another month, or maybe that we can afford. We start Googling how we’re going to be borrowing the money pretty early on.

ALICE: I think something as well is worth noting, and I’ve just really noticed this change, even in just the last six months, that Buy Now, Pay Later providers are working hand in hand with retailers to market products. Even on the Tube, on the way here, I see adverts from one Buy Now, Pay Later provider basically saying, “you can buy everything through us”.

It’s priming us to make all of our shopping choices through Buy Now, Pay Later providers. Because they’re not Buy Now, Pay Later providers are also just payment platforms. You can also pay immediately and pay upfront through them. It becomes this really neat way to make it seem like it’s an innocent payment choice.

PHILIPPA: It’s convenience again, isn’t it? It’s that thing we’re talking about. It’s just seamless. It’s easy. We’re busy. Let’s do that. As you say, particularly if you’re confronted with the advertising the way to work, it feels like a problem solved, doesn’t it?

ALICE: Absolutely. It’s so integrated into the shopping experience in a way that credit cards aren’t necessarily.

£30 bill, or pay £10 today?

PHILIPPA: Do we know how many of us will get into debt to cover the spending that we choose to make over this season?

ALICE: Of those who are actually intending to use credit, 40% are going to use Buy Now, Pay Later. But I think it’s about 50% of us on average that will put some cost of Christmas on a form of credit. It’s just become so incredibly normalised. I started campaigning for more regulation around Buy Now, Pay Later about five years ago. At that point, it was only one-in-five of us that would probably be using Buy Now, Pay Later to pay for Christmas. It’s become massively normalised just over the last five years.

PHILIPPA: That’s interesting, isn’t it? Presumably, thanks in major part to those marketing campaigns we’ve just been talking about.

ALICE: Absolutely. There’s been so much talk about regulation, but at the same time, that hasn’t come into place yet. But they’ve done a fantastic job of capitalising on the moment of relatively limited regulation around marketing and things like that to make us so aware of these providers.

PHILIPPA: And the cycle is, Tim, that whole post-pandemic, it’s five years ago now, but that whole, “you deserve it, cost of living crisis, special times need to be special”. I mean, these firms have leveraged all that, haven’t they? Or it feels that way to me.

TIM: Yeah, there’s a couple of key behavioural things going on with Buy Now, Pay Later. So firstly, it’s free, right? And we just know that that’s going to be impactful in terms of what we choose to buy and how we choose to buy things, right? So the fact that you don’t pay any more if you pay back on time is really important.

The other thing is that because it splits up a big cost into smaller costs, like research shows that just psychologically, we just feel like it’s less expensive. It seems really daft, doesn’t it? I’m looking at a £30 pair of shoes or whatever. If it says first payment’s £10, even though I know [this], I’m an Economist, I should know this, right? I know that I’ll pay three times £10. That’s £30 in total. Research shows that I just feel that that’s actually cheaper.

PHILIPPA: It’s not now, is it? You’re paying £10 now.

TIM: I’m paying later and it’s just £10 now.

DANI: I completely agree with that because in [preparation] for this podcast, I looked at my Buy Now, Pay Later app on the last purchase. It was a £30 product from Boots and I paid [for] it over three months. Why did I do that?

It’s free for you, but someone’s paying

ALICE: Just to say, it’s actually not free. I think we think it’s free -

PHILIPPA: I wanted to ask you that because ‘it’s free’.

ALICE: - but it isn’t.

PHILIPPA: It can’t be free, surely. How do these companies make money?

ALICE: No. Two ways that it’s essentially paying for itself. One is that Buy Now, Pay Later providers are charging the retailers a percentage on what you’re spending, between 2% and 5%, which is quite -

PHILIPPA: From your point of view, do you care if the retailer is paying? Except that -

ALICE: But that cost is obviously being passed to the consumer. Then the other way in which it’s paying for itself is that we know that Buy Now, Pay Later gets people to spend more money. There’s a study from Harvard in 2022 that found that on average, it’s about $60 more per week, a permanent increase in spending, predominantly on retail for people that are using Buy Now, Pay Later. We know it gets you to spend more money.

PHILIPPA: That’s a lot, isn’t it?

ALICE: That’s covering the cost of it. Otherwise, retailers wouldn’t use it. It’s huge. It’s a massive, massive increase. From a behavioural science perspective, I think it’s also worth just noting that it’s effectively decoupling the pain of paying. When you pay for something with cash, if you hand over a £20 note, it effectively triggers the pain receptors in your brain. It feels painful. When you use Buy Now, Pay Later, you’re deferring that payment, so you’re just getting the pleasure of spending the money. It’s a really, really clever way of manipulating your brain into thinking that this is a totally, well, cost-free way of having something now.

TIM: Which is why some debt advice charities advise people to pay in cash wherever possible. That’s increasingly becoming less possible. But if you can pay in cash, you feel the pain more and you end up spending less.

The evolution of frictionless spending

PHILIPPA: It’s interesting because obviously, we’re under this constant temptation to spend. It seems to me in a way that we weren’t even 10 years ago because it’s so easy, isn’t it? Smartphones, it’s smartphones, isn’t it? Because I often just walk out of the house with nothing except keys and a smartphone. I pay for pretty well everything on my phone, and I’m guessing most people do.

ALICE: Yeah, I do. I never use cash, I have to say. I think also what’s changed is just the retail environment. Obviously, online shopping has been around for ages now, but it’s now not only going onto a website to spend money, it’s within your social media apps, it’s on TikTok. Everything is just so, so integrated and jumbled up into this online shopping mess. It’s so easy to be able to just click a button and split a payment. I think it’s no wonder that we’re all struggling with this sense of impulse control in a way to money.

PHILIPPA: Even if you’re physically shopping in a shop, you’re wandering around, you see stuff, you buy. If you’re just waving your phone at the till, that doesn’t feel like spending in the same way, does it? It’s a really different - Even handing over a credit card or a debit card, a bit of plastic, somehow to me, it’s a different psychological contract.

TIM: It’s less friction if you’re not having to put in a pin number as well. The whole process has become lower friction. You’re not forced to feel the pain, as you were saying, and you’re not forced to reflect so much on exactly what you’re doing with your cash.

DANI: It’s a different shopping experience. When you’re on Instagram, they’re completely tailored to what you’ve looked at before - the people you follow, the style. If you get a Marks and Spencers advert, it’s a coat that you probably - That’s your style. You’ve liked a different image before. Because when you walk into a shop, it’s not tailored to you. You have to search. You have to go and find what you like.

PHILIPPA: I’m really interested in exactly how we got here because it does feel to me like this has really ramped up in very recent years. But Alice, give us a bit of history on it, because credit cards, I was interested, 1966 was the first time we had them in the UK. Which obviously it was a long time ago. We didn’t get debit cards until 1987.

ALICE: Yeah, the concept of borrowing has obviously been around for ages. But in terms of [how] we’re looking at frictionless spending and how that’s evolved, it really is only in the last 70 years. So as you said, we’ve had credit cards launched in the UK in 1966. Then online shopping and retail and the ability to check out online seamlessly, well, Shopify in 2006. Apple Pay, which obviously many of us are so familiar with, as you were saying Philippa, the ability to just tap and go.

Also, what’s worth noting is the contactless amounts we’ve seen massively increase. It’s possible to spend thousands now just with a tap. So yeah, Apple Pay came in 2015. Snapchat introduced the ability to make purchases in 2018. Instagram integrated payments in 2019.

In the last five or six years, we’ve seen Amazon Live. So live streaming, a bit like TikTok Shop, selling as they - reminds me a bit of QVC. It’s the new QVC, I guess, on TikTok. But you can pay on your phone while you’re watching it, as opposed to having to send a mail order form off. And YouTube shopping more recently. TikTok Shop has exploded, I think, in the last year.

Where’s the regulation?

PHILIPPA: It’s rolling at an extraordinary pace, isn’t it? You’re talking about Apple Pay. Apple Pay, the start of all this in a way, that’s only 10 years ago. So you wonder where it’ll go. Talk to me about regulation? Because I’m guessing regulation hasn’t caught up.

ALICE: It’s really interesting. The Consumer Credit Act, which forms the foundation of a lot of the way in which credit products are regulated, was put together in the 1970s. It served us well up until more recently, and up until the existence of Buy Now, Pay Later. It’s what means, for example, that when you see an advert for a credit card, it tells you what the Annual Percentage Rate (APR) is going to be and things like that.

It also means you’re protected. If things go wrong, there’s the consumer ombudsman and so forth. With Buy Now, Pay Later, there’s a sneaky little loophole that means that because it’s 0% or free, and because they’re relatively short-term, it doesn’t fall under the regulator’s remit, so it’s unregulated.

PHILIPPA: Completely unregulated?

ALICE: It is. If it’s 0% and if it’s short term, it’s unregulated. That’s changing. As of next year in July, that’ll be regulation day, and Buy Now Pay Later providers will have to stick to certain rules. I’ll say I started talking about the regulation of Buy Now, Pay Later about five years ago, and it was a Wild West. It’s changed significantly since then. Buy Now Pay Later providers are acting responsibly on the whole -

PHILIPPA: So they’re self-regulating to a degree?

ALICE: They are. Absolutely. It’s improved.

PHILIPPA: Presumably because they saw this coming down the road.

ALICE: Completely, yeah. I saw anecdotally some horror stories of teenagers getting debt collection letters five years ago. That obviously wouldn’t happen now.

PHILIPPA: Horrifying.

ALICE: But we’re seeing better protection in the form of affordability checks, which is obviously super important. Protection from the Consumer Ombudsman should come into play in my view, and also reporting to credit reference agencies. Because one of the risks of Buy Now, Pay Later is that there are so many providers out there. It’s very possible to rack up debt across different providers.

PHILIPPA: Yeah.

ALICE: And there’s no communication behind the scenes between different providers to check if you can actually afford it, or maybe you’ve got £1,000 of Klarna debt, but ClearPay are saying, “oh, go for it”. That’s the risk, and we want to see regulation that means it’s treated like any other credit product. There’s affordability checks, and so on.

PHILIPPA: Do we know how much that’s happening? I’m guessing there are people who’ve racked up vast amounts of debt, a lot of people.

ALICE: I’ve gathered about 200 personal experiences from people who had actually got into really, really difficult situations, either 18 year olds who had received a debt collection letter for a scrunchy, they’d forgot to pay back from an online retailer -

PHILIPPA: Wow!

ALICE: - all the way through to people, as you described, who hadn’t really realised that they needed to set up maybe a Direct Debit or made the payment on time. They then had their mortgage application and things like that.

I think an important point, if I can just add, is that the way that these Buy Now, Pay Later products have been packaged doesn’t really feel like debt. It doesn’t feel like credit. They feel like vehicles to purchase things or payment providers. I think that makes people feel a little bit more at ease with using them, but maybe actually it’s worth being aware that it’s a form of credit.

PHILIPPA: Yeah, Tim, that must be a big part of it.

TIM: Yeah, definitely. I mean, even on the details of it as well, there was one survey earlier this year that showed that one-in-two people who used Buy Now, Pay Later, didn’t know that there would be late fees if they missed a payment. This is the key ‘got you’ moment that people have got to watch out for, and maybe half of people aren’t aware.

There’s a lot in terms of awareness and in terms of providers sending better and better communications to people just before a payment is due. Then if you miss one, immediately telling them. Do you want to do something about that? Pretty quickly so they don’t miss another one and so on. There’s a lot that needs to be done on that.

Don’t let technology push you into high spending

PHILIPPA: Because there’s so much regulation can do, it seems to me, to separate us from this convenience. But then the technology doesn’t let you go, does it? Off the back of one of the podcasts we did earlier in the year, we had a fantastic guest who said, “look, if you want to rein in your spending, put stuff in the basket, don’t buy it. Wait 24 hours or whatever, and then consider, do you really want this stuff or not?”

It’s remarkably effective, I think. I was doing that. Then, of course, what you get is you get basket reminders, don’t you, in your email? “Items in your basket”. I mean, it’s amazing. They hunt you down, don’t they?

TIM: Yeah. In general, we want to make good decisions easier for ourselves and bad decisions harder. We’re probably in a really good place to judge what is going to be a good decision for ourselves if you step back and think about it. Maybe a good decision is spending less on online retail and maybe using less Buy Now, Pay Later.

How do we make those decisions to delay easier? It could be through setting things up on your phone, so it’s harder to spend money on your phone, so you have to go back and use a laptop or whatever. That’s quite a big friction moment. It could be imposing those delays on yourself, but also just talking to people as well, that mutual accountability, it can be really important for people.

PHILIPPA: I was going to say, I think there’s quite a lot you can do with settings, aren’t there? Which I am all over on everything. The whole absolutely not to cookies, the whole making sure that trackers are stripped off all your devices, all those things that make it harder.

ALICE: Unsubscribing, from marketing emails.

PHILIPPA: Unsubscribing from marketing emails. Don’t you get a real dopamine hit when you unsubscribe? When I unsubscribe from things, when they rain me with stuff I don’t want, and then you unsubscribe and you get this lovely clean inbox with all this stuff.

ALICE: It doesn’t last long, that’s the crazy thing. Then you sign up for a 10% off and you’re getting more. I think also it’s important to note that there are obviously lots of things we can do to help ourselves manage our spending. But we often forget that this isn’t just about us vs. our impulse control. Behind the scenes, when you’re hovering over the ‘Pay Now’ button, billions has been invested in trying to get you over the line.

It reminds me of, I always think about in the Devil Wears Prada, she’s talking about the cerulean blue lumpy jumper, and she’s like “what you don’t realise is that this jumper has been chosen for you by this whole invisible machine”. It feels similar to that where billions has been spent in precision engineering and data science and behavioural science to get you to spend money. It’s not as simple as just saying, “have better impulse control”.

Masterclass on proper usage

TIM: All that being said, Buy Now, Pay Later does serve a real purpose. I think it does help a lot of people make those bigger purchases. Also, if your income isn’t constant. One of my friends is a top lawyer, she’s self-employed. She’s probably very well-paid. Actually, because she’s self-employed, her income is very lumpy. She might not get anything one month, then an absolute tonne the next month. Being able to use things to smooth those purchases is really helpful for her.

PHILIPPA: That must be true. I’m wondering whether we shouldn’t have a little masterclass on how to use it properly then.

DANI: Well, I wouldn’t use it as a shopping app because I’ve noticed on Klarna that it’s like Amazon. There’s categories, you can shop through it. So don’t use it like that.

ALICE: Delete the app, I’d say -

DANI: - Not if you have payments on it that you need to repay. But if your balance is clear -

PHILIPPA: - It’s really important not to do that.

ALICE: You don’t have to be constantly bombarded with notifications. Even just doing it analogue and keeping reminders and putting them in your calendar as to when payments are due, I think is essential.

PHILIPPA: Because both of you said that you tripped up over when payments should be made. It’s so easily done. You’re really savvy people. What hope is there for the rest of us?

DANI: Also, maybe set yourself a limit. Everybody’s circumstances are going to be different. But if it’s £500, OK, if an item is over £500, then I can spread the payment. Maybe think of it like that.

PHILIPPA: I like two-factor authentication on payments, which is annoying. This way, you have to do the two steps thing and they WhatsApp you, or they text you, or you have to use an authenticator on your phone. But it does put that hiccup in, doesn’t it? Before you just click and go.

TIM: Yeah, I do, I’m most tempted to make irrational purchases of books on Amazon. I have to factor it, stay logged out. That friction forces me to delay a bit. I mean, I probably do still do the occasional impulse purchase, but it’s going to be much less than one-click buy.

DANI: One step before putting it in your basket on most shopping apps, ASOS Boots, things like that, you can favourite stuff. Maybe that’s a step before putting it in your basket and having a think, just favourite the item. You’ll still get a notification saying, “remember you favourited this”, or “now it’s on sale”. But maybe that’s a nice way of going, “OK, here’s my shopping list. These are the things I like”. A week later, come back and be like, “I don’t need any of these things”, or “I just need that one thing”.

ALICE: Oh, I know. They’re so clever with then sending - I need to turn them off, actually. This is a good reminder. In app notifications, just saying, oh, I got one the other day. It was like, “we really think that you’d like a hot tub”. I was like, “I don’t know how big you think my garden is”.

PHILIPPA: Why would they say that to you?

ALICE: Maybe that’s less effective marketing, but there have been somewhere, it’s like, “oh, you’re absolutely right. I did need that thing”. They’re just so clever. I think I like to try and bring things back as analogue as possible and use wish lists for keeping track of things I want to spend money on. I think also giving yourself permission to have guilt-free spending. I think things like that can help free you a little bit to splurge when you want to rather than controlling all of your spending. I think it would be quite helpful.

PHILIPPA: What do you reckon, Tim?

TIM: Keeping a budget is done by a lot of people and it can be really helpful. That’s one of the things that debt advice charities would advise as well. I think it’s also worth pointing people to free debt advice as well, because often through using Buy Now, Pay Later or credit cards or whatever else, we can end up in a situation where we’re in financial difficulty.

The research shows that when we’re in that situation, we feel things like anxiety and depression. We might even feel embarrassed or even worthless. So there’s some really heavy emotions going on.

Actually, it’s important to realise that actually, that’s entirely normal in that situation, you’re not alone and that you can go and get free help which will help you become debt-free and take control of your finances. There are free charities out there like StepChange, which are really familiar with helping people out of these traps.

ALICE: Can I just mention something else as well? Because I touched on being really analogue. There are also really positive technologies that can steer your decision making in the right direction.

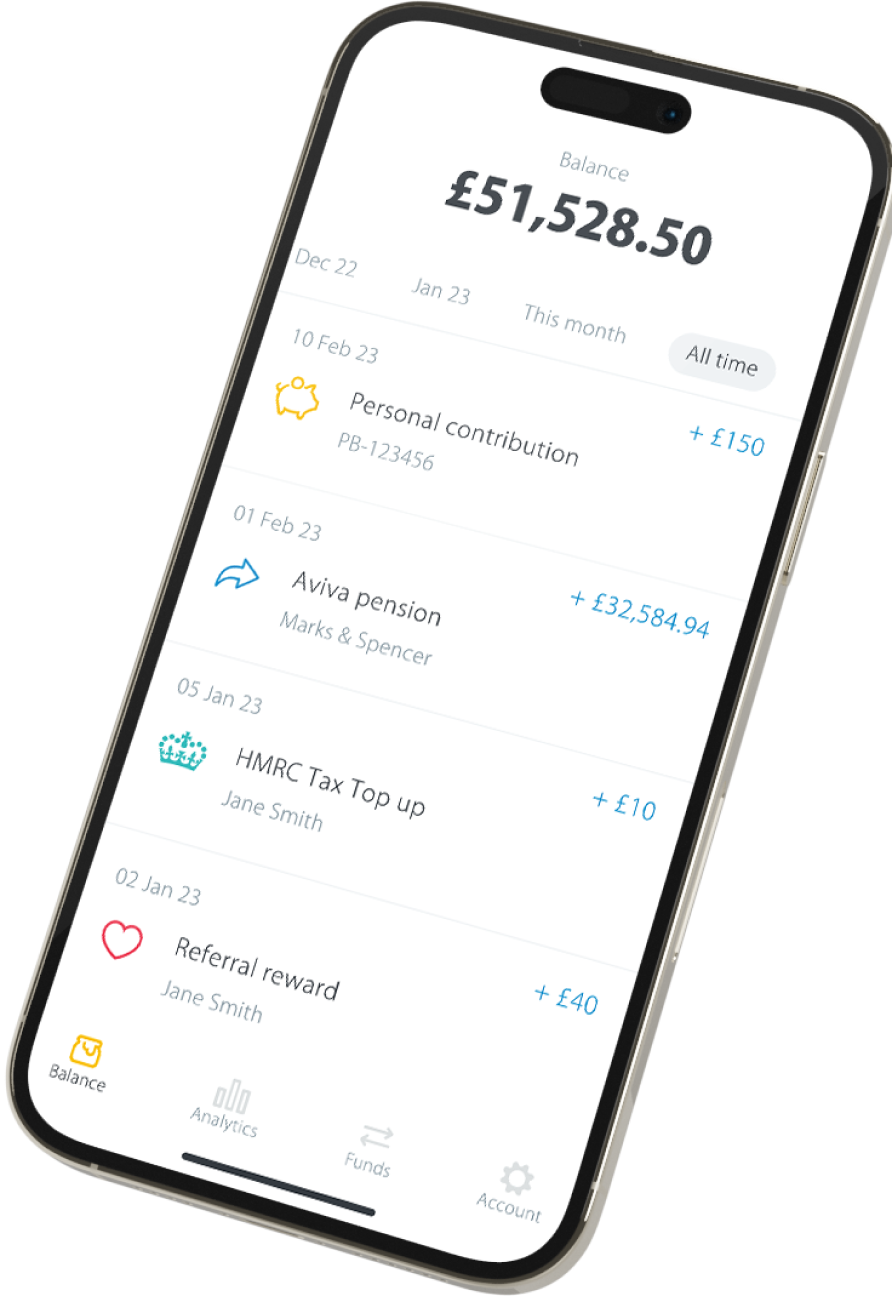

I’m a huge fan of Open Banking apps and lots of banking apps themselves now integrate features that nudge you into automating your savings, for example, or even saying, “oh, you spend a little bit more this month”, or actually turning on the notification so that when you’ve made a purchase through Monzo, so or whatever it is, it actually says you’ve made the purchase. It just gets you more familiar with where your money’s actually going.

TIM: These digital tools are fantastic. I’ve got a budgeting app, and I got one that didn’t allow me to make payments anywhere else. When I go on it, it just helps me budget. It’s not there for me to make payments or to look at things. It’s just there to help me understand what I’ve spent on different things over the course of -

ALICE: - Which one that’s really asking?

TIM: I’ve got Snoop.

ALICE: Oh, yeah, I love Snoop. It’s great. Snoop and Emma are the two I know of. Others are available.

Dopamine hit of saving money

DANI: I think as well with the dopamine hit you get from buying something, you get that from saving.

PHILIPPA: Yes!

DANI: I started a challenge in January on Monzo. Other banks are available. It was a one-penny-a-day savings challenge. I’m thrilled -

PHILIPPA: - Oh yeah?

DANI: - When I look at that pot now. By the end of the year, you’re supposed to have, I think, £648. At this point in the year, I’ve got hundreds of pounds. It started a penny on 1 January, two pennies on 2 January, and it goes up like that -

PHILIPPA: Oh, OK.

DANI: - Now the daily payments are £3, something.

PHILIPPA: It’s a coffee.

DANI: Less than a coffee.

ALICE: It’s so clever.

DANI: It’s completely changed my mindset in terms of saving up for stuff.

ALICE: There’s one with Monzo. For anyone that enjoys the gamification of money, you can use a tool called ‘If This, Then That‘. For example, you can set it so that if it’s raining outside, you automatically save £10 and things like that, which is just - If you find money managing it quite boring and tedious, I think finding ways to actually make it fun. Yeah, why not?

PHILIPPA: But you’re right about the dopamine hit of saving, which I know sounds so hilarious, because how can that compare to going out and buying a handbag or something?

DANI: It really does.

PHILIPPA: But actually, it really does. It’s so weird. I get a sad little hit every month when I see my pension contribution land in the account. It’s really fascinating. It’s just that - Because I’m not one of those people who lives all over my pension balance. I don’t live on the app looking to see what it is. I know some people do and find it very rewarding.

But that, I do. I get a little warm glow. It’s safely gone and stashed. As you say, the saving thing, when you look at those little automated savings pots, I’ve got them set up to small amounts going in and it’s amazing how they rack up.

DANI: Yeah, it is.

PHILIPPA: Then if you don’t look very often, when you do look -

DANI: - it’s a nice treat -

PHILIPPA: - It’s like a lovely win.

DANI: It’s that consistency. We say it all the time about pension contributions, but the same for saving. Consistency and automation are the two biggest things. If you’re listening and thinking, “oh, I want to start saving”, or “I want to start paying off this debt”. If you just start with £10 or whatever, it’s a very small amount, you won’t notice it’ll just start rolling. I think the main thing is [to] just start now.

ALICE: I think also - Sorry.

PHILIPPA: If you don’t see it, you don’t miss it, do you?

ALICE: I think translating because with Buy Now, Buy Later, it’s very obvious what the tangible win of using it is. You’re seeing, “oh, I’m going to get that new top”. Now, I think, if you can also translate the opportunity cost. We’ve said the average increase in spending for the average person that’s using Buy Now, Pay Later, it’s $60 extra per week that the research has shown.

PHILIPPA: I’m still amazed by this.

ALICE: I know.

PHILIPPA: It’s a lot.

ALICE: It’s a lot of money.

PHILIPPA: It’s so much.

ALICE: It’s so much money. That’s three - quick maths, but £3,000-ish a year. I think translating into the opportunity cost of what that means over the course of a year, maybe even over the course of 10 years, it starts to actually look quite scary, which you don’t want to scare yourself into saving. But I think having a more tangible connection to what you could have otherwise can be really helpful.

PHILIPPA: What that money could’ve done for you.

ALICE: Exactly.

PHILIPPA: I’m going to say, I know we’re a pension podcast, I’m going to say, if you’d invest in that way, it would’ve been sitting there rolling for you. So there’ll be even more of it.

Tips for managing seasonal spending

PHILIPPA: I’m just going to wrap this up with [the] best tips. The tip that you’d have for this season right now, reining in your spending.

DANI: Mine’s maybe a bit basic, but Secret Santa. I think, don’t feel like you have to buy a gift for everybody. If you have a big family, Secret Santa’s fantastic. If you have a small family, it’s even better because you can get a really nice gift.

PHILIPPA: Yes. Excellent advice.

ALICE: My mum actually messaged me yesterday, the best message ever, which was, “we’re doing Secret Santa this year”. I was thrilled. I think that’s a massive one. I think also, it sounds really boring, but just planning. Actually sitting down and writing a list of what you’ve got to spend money on, who you’ve got to buy a present for, and thinking really carefully about what the budget is, and then going out and making purchases. I think it’s boring, but really, really important.

PHILIPPA: Yeah. Go on then, Tim.

TIM: Definitely agree with all those. I guess one other thing is if you think it’s going to be really problematic, speak to someone and get help. It’s better to do that now before Christmas rather than wait until January.

PHILIPPA: Yeah, definitely. Thank you all very much indeed. Such a great discussion. I really enjoyed it. I learned loads, as I always seem to do.

If you enjoy these podcasts, we’d love to hear from you. You can contact us on social media @PensionBee or email us at [email protected] with your thoughts and questions! We would really like to hear your thoughts and questions.

If you’re new to the podcast, you can find all the back catalogue episodes on YouTube. They’re in the PensionBee app too, or whatever app you prefer. While you’re there, you could always leave us a review and a rating.

Next week, we’ll have a special episode all about - what else? The Autumn Budget. What does the Chancellor have in store for us? In December, we’ll be rounding off the year with an episode about micro-retirements, and we’ll be looking back at everything we’ve learned this year with a special bonus episode, keeping your finances and your retirement savings on track. Don’t miss those.

A final reminder, anything discussed on the podcast shouldn’t be regarded as financial advice or as legal advice. When investing, your capital is at risk. Thanks for being with us. We’ll see you next time.

Risk warning

As always with investments, your capital is at risk. The value of your investment can go down as well as up, and you may get back less than you invest. This information should not be regarded as financial advice.